How banks are tackling the “Frankenstein” workaround

Banks across the globe have taken various approaches in their digital transformations to date.

Sber is taking an all-in-one-platform, “Big Tech”, approach since dropping the “bank” from its name, and investing in lots of smaller companies before eventually buying them.

ING decided to grow fintechs internally so it could use their technology and benefit from their profits at the same time.

Banco Santander is throwing a whopping €20 billion at its digital transformation over a four-year period to transition its architecture to a multi-cloud environment and adopt agile methodologies.

Resisting “Frankenstein” workaround

“The future of banking lies in a modular approach,” says Fineco

Historically, banks’ digital transformations have resorted to “a Frankenstien workaround”, according to Jay Hunt, platform head at fintech-as-a-service start-up Yabota.

Hunt explains that legacy core has long constrained banks, because they’re “too scared to remove it”.

“They wrap it in something modern, but that only goes so far,” he tells FinTech Futures. “Ultimately, it’s still just that core product.

“So you’re left with a Frankenstein workaround which compounds the problem rather than improving it. You need to break down the monolith into micro-services.”

The reason for this half-baked approach is partly down to a hesitancy to fully invest in a new, expensive tech stack.

But as Vikas Srivastava, chief revenue officer at Integral, tells FinTech Futures: “Legacy technology actually ends up being more expensive in the longer-term due to ongoing upgrades and maintenance.”

The micro-services approach

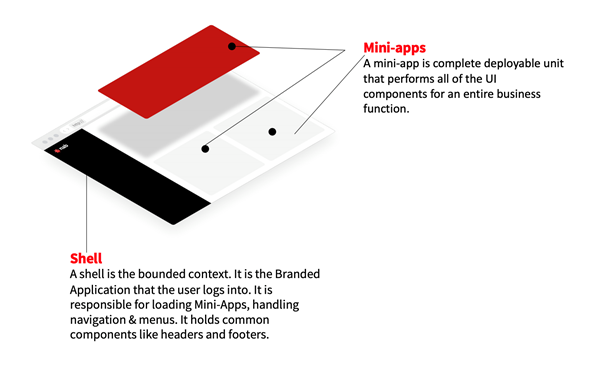

NAB is building a user experience (UX) platform – a multi-year project designed to take a more modular approach to application development.

“We realised that decomposing our monolithic frontends into micro-frontends […] would be worth exploring,” the bank said back in September.

NAB calls these micro-frontends “mini-apps”. Each mini-app can rest on multiple applications, regardless of the mini-app’s own hosting location. This is what makes them easily reusable.

The bank envisions a platform where third-party developers can build on the UX platform, acting as a sort of ecosystem through which fintechs can access NAB’s customers.

NAB’s micro-services approach

“The future of banking lies in a modular approach as it enables banks to be agile and align with what customers need, quickly,” says Fineco, another bank modelling its structure around micro-services.

The more third-parties a bank opens up to, however, the less control it has over its technology stack.

Though as Hunt adds, “the more open your ecosystem, the more you can scale”. Because of this, he says imitating the Big Techs can be “good”, as they’re the best at scaling, managing, and maintaining their technology.

The Big Tech approach

But for one bank, merely imitating isn’t enough. Over the past few years, Russia’s largest bank – Sber – has been buying up start-ups to flesh out its Big Tech approach.

Pursuing a closed, rather than open, ecosystem, Sber wants to be everything to all 100 million of its customers.

Having been rebuffed by one of Russia’s Big Tech firms – Yandex – the bank has decided that if it can’t buy a Big Tech, it will become one instead.

Sber’s chief technology officer (CTO), David Rafalovsky, told FinTech Futures in November that these acquisitions have sparked a certain perception of the bank.

“People think we just bought a load of start-ups and slapped our name on them – but that’s not how it is.”

By buying the technology, rather than paying software providers like Microsoft or AWS, Sber will eventually morph into a Big Tech itself.

“There is a lot of pressure right now for banks to become more like tech companies,” says Inetgral’s Srivastava. But is Sber an example of this pressure going too far?

Fineco thinks there is a balance to be had. “Although technology is a vital part of driving the customer experience, it cannot replace banks themselves,” explains Marco Mottadelli, head of global brokerage at Fineco.

“Established banks have proven models, but the two can work together to achieve a stronger result.”

The DIY approach

Still in its embryonic stages, fintechs are starting to emerge which help banks be the developers of their own technology, providing them with the standardised platform on which to build.

Banking-as-a-service (BaaS) providers licence banks their technology through white-labelled, out-of-the-box solutions. But start-ups like LemonTree Software are taking a different approach.

Co-founder and chief commercial officer (CCO), Jamie Nascimento, told FinTech Futures back in July that there is “a real desire for change from people on the inside” of banks and financial institutions.

This is because most fintech software companies charge firms based on usage and features. Which is almost always expensive, and involves long contract processes every time another feature needs to be added.

“We believe that recognisable and [a] highly competitive service is better developed internally,” says Fineco

Fineco agrees with this methodology. “We believe that recognisable and [a] highly competitive service is better developed internally,” says Mottadelli.

“Keeping Fineco’s value chain in house allows the company to be independent, efficient, and reactive in changes and improvements and building a core service knowhow.”

Lemontree, which launched its first product back in September, allows banks’ developers to code into the platform. Banks pay a flat licence fee for the platform, meaning no matter how much they scale products on it, no extra fees are incurred.

The third-party approach

Perhaps the most familiar of the approaches banks have taken is the third-party approach, and it’s one which can often fall into the pitfalls that Hunt summarises as “the Frankenstien workaround”.

Aleksander Leicht, Elavon Europe’s banking alliances head, talks about the “fintech mindset” banks have embraced to separate out customer journeys – such as a bank account, getting a loan, starting a business, or setting up payments.

“In turn, some have moved away from building many of these digital capabilities themselves, and instead are turning to third-party or white-labelled financial services,” Leicht tells FinTech Futures.

BaaS providers like solarisBank, Modulr, and Railsbank are part of a burgeoning market. It’s projected to grow by $7.07 billion over the next three years according to a Technavio report.

So, which banks are getting the third-party approach right? Chief business officer (CBO) at Yolt Technology Services (YTS), Leon Muis, told FinTech Futures in February that it comes down to how they work with APIs.

Banks want to make it work in theory, but their mainframes have made it hard, he says.

“Traditionally banks hoarded customer data, but now they’re suddenly being asked to open it up and consume third party data too,” Muis said.” They should see API as another channel.”

Muis mused that one day “it might be the quality of the API which determines account switches in the future”, which he says “will be a nice end point for open banking”.

In other words, the banks which are lagging behind in their third-party connections are ultimately the ones which will lose their customers to the competition.

Read next: Digital banking platforms – the new core