Privatbank’s CEO talks turmoils and turnarounds

Privatbank, Ukraine’s largest bank, has a colourful history. Founded more than 20 years ago, the bank reached dire straits in 2016 when it failed stress tests and was deemed undercapitalised.

Investigations later found ten-year evidence of “large-scale and coordinated fraud” and a $5.5 billion hole in the bank’s balance sheet.

The bank was nationalised, leaving the hands of oligarchs Ihor Kolomoisky and Gennady Bogolyubov.

The former owners have since launched a series of legal cases against the bank to undo its nationalisation, which became legally irreversible in May this year.

Privatbank’s CEO Petr Krumphanzl

The state-owned lender, which is headed up by Petr Krumphanzl, is still pursuing claims worth billions of dollars against these oligarchs.

$5.5bn hole to profit

Despite its troubled financial history, Krumphanzl tells FinTech Futures that Privatbank is “not bureaucratic or slow as you might expect from a state-owned bank”.

The CEO helped bring the bank back from its loss-making days in 2016 to the country’s most profitable bank once again. The bank accounts for 60% of profits in the whole Ukrainian banking sector.

In 2019, the bank’s net profits jumped 2.5 times to $1.2 billion (UAH 32.6 billion). It allowed the bank to channel 75%, or $930 million, of 2019’s profits to the national budget as dividends by 20 June 2020.

But coronavirus will likely impact the bank’s revenues this year. The number of loan applications did fall “dramatically” in April for Privatbank. This was due to businesses being “more conservative” during the crisis, Krumphanzl explains.

He says the bank responded by cutting interest rates – partially subsidised by the government – and offered loan holidays and restructuring on as individual a basis as it could manage.

Culture shake up

Since the bank’s nationalisation, Krumphanzl says it has “dramatically” changed the organisation of its internal teams.

“It’s not a top down structure anymore,” says the CEO. “And we don’t like to be called a bank, rather an IT company with a banking licence.”

Krumphanzl testifies that this shake up has bred more intense innovation in the bank, “something nobody expected” after its nationalisation.

Privatbank runs an internal competition called ‘Digital Safari’ where employees put forward their ideas and compete with each other.

The best ideas are then implemented in the bank, and the creators are rewarded with courses at Stanford University.

“They do something for us, the bank does something for them,” says Krumphanzl. “This is a big change of the bank’s corporate culture.”

Privatbank’s Digital Safari

One project saw the bank try to engineer a ‘cashless village’ in a small Ukrainian city. The bank paid older generations to use cashless services but found that this doesn’t work “even when you pay them”.

It also gave each child a payment card through their school, which it found a much better engagement path.

These children then persuaded older generations to use the cards too. This is a trend UK challengers like Monzo are now seeing as their millennial customer base spread the word across age groups.

Proud of the way Privatbank has come since 2016, Krumphanzl is adamant that the bank has proved wrong the expectation that it was just going to be “another uninteresting savings service”.

“Main concentration” on digital

Whilst the bank does maintain a large branch footprint (2,500) to reach its rural customers, the CEO says its “main concentration” is on digital channels.

After the bank was nationalised, risk management, compliance, anti-money laundering (AML), and public communication systems were developed “more or less from scratch”, says Krumphanzl.

“We do almost everything in-house,” says the CEO. “That way, we can be fully in control. We don’t need to wait for suppliers. And it takes weeks not months to launch products.”

The bank houses an IT team of more than 1,500. The Ukrainian bank’s model is informed in part by its Asian-Pacific neighbours.

Around two years ago, a group on the bank’s executives travelled to China and met “strategists of major tech companies” in the region, the CEO explains.

At this point, the bank had built the first iteration of its mobile and online banking service Privat24. It sat on pre-existing software in the bank.

But after its China visit, the state-owned lender launched a new version based on new, “flexible” infrastructure and a new design.

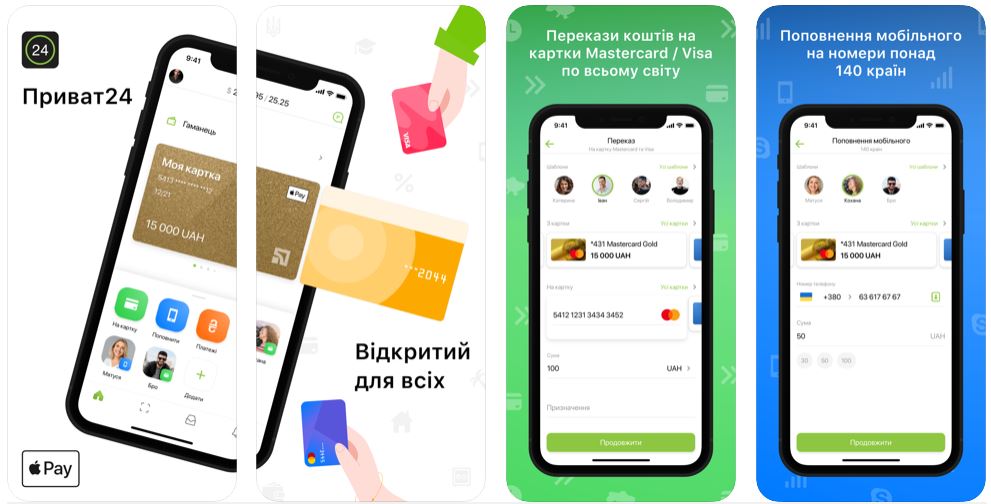

Privat24

Today, Privat24 provides 147 different services. Designed like a marketplace, it resembles the ‘super app’ model of Asia Pacific players such as Grab.

Financial services include international transfers, ability to pay bills via the app, credit checks, car, home and cash loans, various insurance products, and business accounting tools.

Privat24 on the Apple Store

Due to an agreement the bank made with Ukraine’s police, car owners using Privat24 can prove their insurance via the app, rather than through papers they keep in the glove box.

Google and Apple Pay can be accessed from within the app, something Privatbank’s CEO claims “wasn’t on the market before”.

Users can also order food, buy tickets for events, make a doctor’s appointment, and shop through the app.

“We have a well-functioning digital channel,” says Krumphanzl about Privat24. “The question now is how to make clients use it more.”

In 2018, the app had nine million Privat24 users – more than 20% of Ukraine’s population. The CEO says the bank is now the “biggest seller” of tickets in Ukraine, and that Privat24 has gained nearly two million new users since 2018.

The bank’s app has seen a “30% increase” in number of transactions during coronavirus, according to Krumphanzl. This is likely due to the bank’s message push that going to branches is dangerous.

“The future is biometric”

In February, Krumphanzl told KPMG that he thinks “the future is biometric”.

Asked what this looks like at Privatbank, the CEO reveals that the bank is working with three retail networks to provide them with biometric infrastructure.

“We understand that in a few years, people won’t want to use computers and mobiles for everything,” says Krumphanzl.

The retailers are using bank-provided tablet software to allow shoppers to pay using their face. The partnerships are currently in “pilot” mode, with the bank still “verifying if clients like it”.

“We call it pilot but it is fully operational,” the CEO explains, “we just don’t use it on a mass scale”.

The bank is also working on biometric software for ATMs. It’s looking at the potential for face, fingerprint or voice analysis to transact.

Read next: Credit card challenger Koto to launch in UK come 2020