As platformania reaches its peak, what is the secret to marketplace liquidity?

Platform businesses are exceedingly lucrative. Over the last ten years, the platform business model has risen exponentially in popularity causing a highly saturated market and what the Harvard Review has described as ‘platformania’.

Platforms are all the rage

The space, it explains, is “a land grab where companies feel they have to be the first mover to secure new territory, exploit network effects, and raise barriers to entry.” But as a result of extreme competition, the rate of failure is high. The average lifespan of a platform business in the US market is just 4.9 years with many gig economy platforms collapsing even faster, within just 2-3 years.

One of the major causes of this is the lack of marketplace liquidity – “a state where there are a minimum number of producers and consumers on the marketplace and there is a high expectation of transactions taking place.” More simply, it is when a platform does not have enough supply and demand for their product/service to succeed.

There are numerous elements that contribute to achieving marketplace liquidity. Some are more powerful than others and their importance varies from vertical to vertical but three that are common to almost all platform businesses are geography, building trust and network effects.

Location, location, location

The importance of location-tech is none so clear as in the example of Uber. When Uber launched, it maximised on location data to disrupt the taxi and ride-sharing industry – and then used the same data to scale into different cities, countries and verticals (Uber Eats). At the latest Paybase Workshop, Paul Cook, the growth and analytics advisor for Hiyacar, Esme Loans, Licklist and more explained:“Data is fuel. But data plus location used well can mean real acceleration beyond your competitors.” However, geography can easily be misunderstood when it comes to marketplace liquidity.

It is not just the physical area of distance that is important to conquer (e.g. Tinder being available in multiple cities) but the limits of the area that transactions will fill (i.e. how far people are willing to travel for the product/service). If Tinder acquired 1,000 female heterosexual users in Leeds, for example, and 1,000 male heterosexual users in London, its liquidity would remain the same. It is unlikely that users in Leeds would either travel to London for the service or set their location settings to a radius wide enough to make London users visible. For this reason, the number of users cross-city would not affect the business’s overall liquidity. However, if Tinder acquired 500 male and female heterosexual users in a single city, the liquidity would rise with the increase in user density. In order to succeed, therefore, platforms like Tinder need to scale with a city-by-city launch strategy.

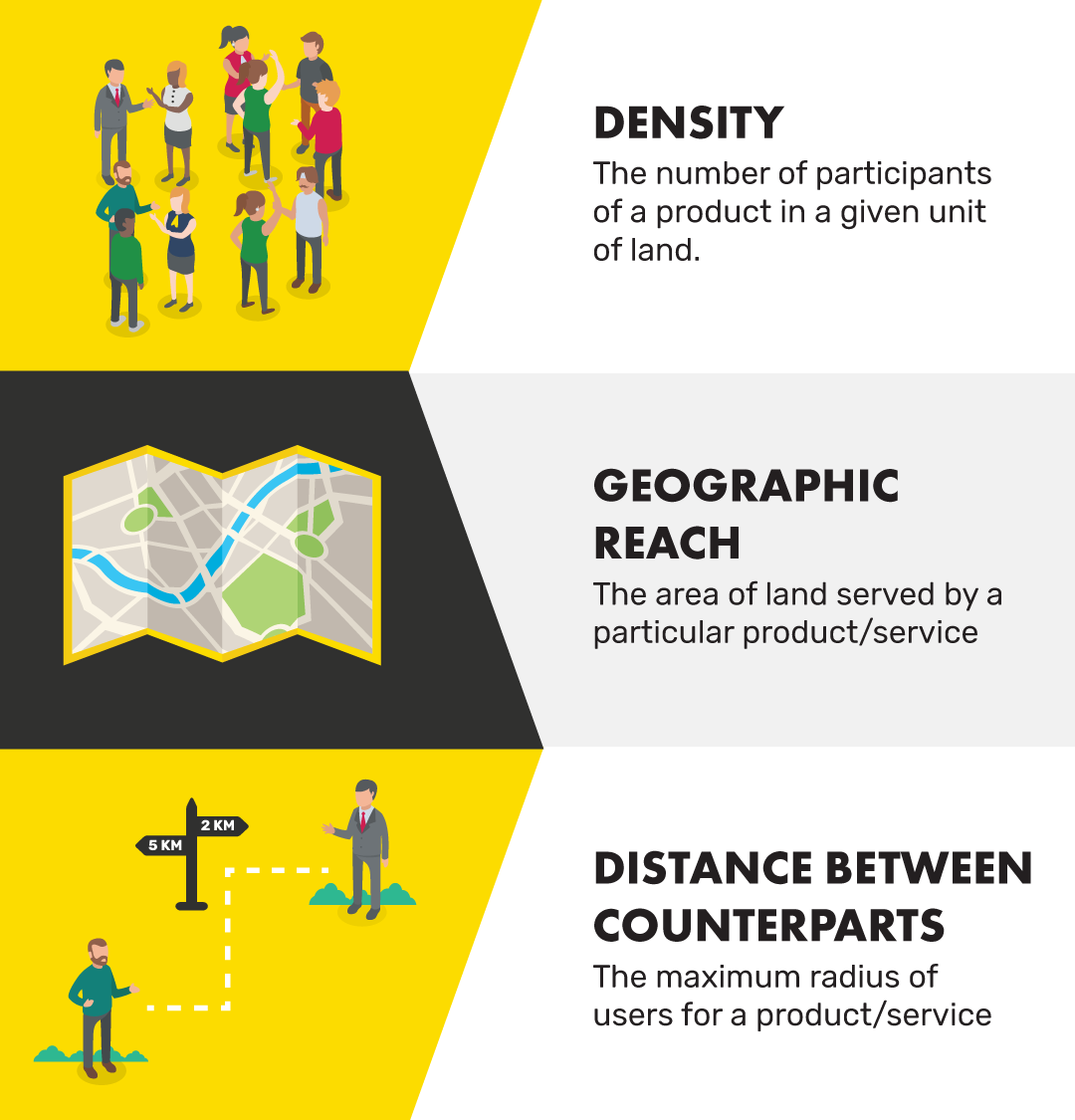

TechCrunch names the three main components of geographical liquidity as density, geographic reach and distance between counterparts.

“When you think about liquidity,” Cook continued, “think about how you measure it. Think about the quality of transactions, the cost-effectiveness of transactions and the probability of repeat transactions.” If users are too geographically spaced out or there are too few of them, liquidity is difficult to achieve. A very simple hack could be using a circular catchment area so that all of a business’s geographical extremes are equidistant. If Tinder’s geographic reach and distance between counterparts was too wide, for example, its users would not travel to use the service; if their user density was spread too thinly, there would be fewer results available to those using the app. It is therefore of paramount importance for platform businesses to consider geography because it is key to determining a product’s potential for adoption and scale.

In strangers, we trust

By nature, platform businesses force users to put their trust in strangers – whether that be gig/sharing economy platforms, online marketplaces or any other platform model. Without trust, it’s almost impossible for a platform to attract users but trust is difficult to establish as a small, emerging brand. Like geography, trust is tricky to maneuver and it causes many platforms to fail in their early stages.

There are several hacks that can be used to build a business’s reputation such as focusing on a niche target audience (e.g. a pet food online marketplace that exclusively targets Labrador owners) or focusing on a single vertical (e.g. Habito for mortgages). Another approach is what’s known as ‘single player mode’, which was a strategy used successfully by Amazon.

Single player mode is the process of establishing one side of a marketplace (e.g. sellers) before introducing the other (buyers). Jozef Wallis, former founder of dental appointment booking platform, Toothpick, and co-founder of Booxscale explained that to achieve liquidity, they launched a B2B offering before their consumer-facing product. “When you balance marketplaces,” Jozef said, “you need allies and you need early adopters – those willing to try a new system.” Toothpick began by signing up dentists to its platform and, once it had built a strong reputation and user-base, they were ready to launch their product onto the consumer market.

34% of the top 100 marketplaces had some type of single player mode as an initial value proposition. Amazon is perhaps the most prominent example. Before Amazon launched its marketplace, it was a successful retailer. It bought from established bookstores, publishers and independent sellers. In doing this, it was able to aggregate a lot of trust for buyers and, with its existing trust capital, it launched Amazon Marketplace in 1999. Today, Amazon is forecasted to join the $1 trillion valuation club along with Apple and Microsoft.

And finally, network effects

Network effects are “the phenomenon whereby increased numbers of people or participants improve the value of a good or service.” An example of this is Facebook – the more users that join, the more valuable the network. It may come as a surprise to hear that when it comes to platform network effects and liquidity, the gold standard is Craigslist, the online directory that hasn’t changed its product or interface since it launched in 1995. Nick Fulton, head of partnerships at Paybase explained that this is because “Network effects are severely underestimated.” Despite the lack of UX, features and the historic reputation of Craigslist, its user base is so strong that it outweighs all of its competition.

Network effects generally operate on a winner-takes-all basis. This was key to the success of Uber. In 2018, Uber was sued by Sidecar, an early ride-hailing competitor, for allegedly using “predatory pricing and fake bookings to put its rival out of business”. Uber’s tactics (that included paying drivers high rates and charging riders less) resulted in it monopolising the market early and, with these network effects, they wiped out the competition.

Network effects are closely intertwined with both trust and geography and they can be built by integrating features that enhance trust in a platform and that utilise geography to optimise a platform’s relevance. Uber’s fare splitting is a good example of this – the more riders in their network, the more value that came from the split fare feature. “Lots of companies provide the option to split a bill,” Nick explained, “but this only works when everyone is on the same network.”

Why payments could save the day

When marketplaces began, their function was to connect buyers and sellers on a platform e.g. Gumtree. As they evolved, more features and services were added until eventually, payments and delivery were integrated into the platform infrastructure (e.g. Airbnb or Deliveroo). This gave platforms access to transactional data including quantity of transactions, IP addresses, delivery details etc. This was not only invaluable to streamlining CX but it helped businesses to make their products more intuitive and to add liquidity-enhancing features.

But building a payments framework from scratch is not a simple task. For many businesses, SMEs in particular, the process is long, costly and restricted by legacy technology and thinking of traditional financial institutions. That’s not to mention the regulatory requirements that must also be taken into account. These processes can, at best, prevent some businesses from building the product that they want and, at worst, prevent others from reaching market altogether.

Balancing liquidity is crucial for businesses in the platform economy. But if a business is focusing on building a compliant payments infrastructure, it takes away from the time they could be spending on all-important innovation. Partnering with a payments provider, alternatively, gives businesses the all-important time and resource they need to focus on product innovation and to stand out from their competition.

So, what’s the secret to marketplace liquidity? It varies from business to business. Generally speaking however, it is not just the combination of geography, trust and network effects that gives a business the tools for success but having the time to innovate with them without being waylaid by financial and regulatory obstacles. As well as resources, a strategic, experimental approach has helped the success of platform industry giants – and it is this that can be the key to disruption.

By Anna Tsyupko, CEO and co-founder, Paybase