Payments: contactless charitable cases

Charities large and small are waking up to the need to embrace contactless payments. Banking Technology looks at the drivers, challenges and opportunities.

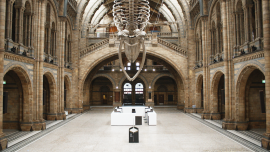

On the streets of Amsterdam and Rotterdam, rough sleepers have been provided with winter coats incorporating contactless payments technology. In the London Boroughs of Hackney and Islington, people experiencing homelessness have been given portable terminals. In the Natural History Museum in London, a contactless terminal under the iconic blue whale skeleton in the main foyer has proved a success.

These are all pilot projects but there is no doubt that the charity and not-for-profit sector is now rushing towards contactless payments, for good reason. As people carry ever less cash, particularly in metropolitan areas, so many charities have seen a steep reduction in donations. While there are undoubtedly other factors as well, consumers have become comfortable with contactless in an extremely short space of time and studies have shown that many would now favour this method for charitable giving.

The rationale

A survey of 2028 UK adults carried out for Barclaycard in January 2017 by YouGov concluded that charities could be missing out on more than £80 million in donations each year by only accepting cash donations. Around 42% of respondents said they carried less cash now than three years earlier.

Andrew O’Brien, co-founder and CEO at specialist fundraising technology company, GoodBox, points to the drop in charitable giving in the UK in the last ten years from 0.75% of GDP to less than half a per cent. “You can assess the reasons but I’d strongly argue that it is not because things are getting any better, there are now more homeless people than the population of Newcastle,” he says.

As well as a reaction to the demise of cash, the contactless approach provides reassurance for the donor. In the Dutch example, run by the Helping Hearts charity, the integrated patch in the winter jacket enables people to transfer one euro per tap using the NFC technology. After the donation, donors receive a payment notification in their bank account, with a personal thank you from the homeless person.

The homeless person can only spend the money in the account through an official homeless shelter, for a meal, a bath or a place to sleep. They can also choose to save the money and spend it on bigger goals, such as training courses, or might choose to keep it per se, to start to build some savings. This controlled spending model addresses the concern donors may have about how their money will be spent.

The approach also brings recipients into the financial services sector, from which they are often excluded. For instance, the UK’s long-standing Big Issue magazine, which empowers homeless people but has seen a steep decline in sales in the last few years, is also trialing contactless and the proportion of the cover price that goes to the seller will credit a bank account.

In fact, an individual Big Issue seller was ahead of the charity. In 2016, Simon Mott, a former London Underground driver who had been selling The Big Issue outside South Kensington tube station for the previous five years, invested £59 in a card reader from Swedish firm iZettle so that he could take card payments using his smartphone after seeing a steep decline in the number of people carrying loose change.

The route being taken in Hackney and Islington by charity, TAP London, has the same reassurance but with a different approach. “We first wanted to take contactless and use it in an applied way to create a new model,” says co-founder, Katie Whitlock. Having trialed NFC terminals with volunteers over the summer, the charity has been piloting them with homeless people.

She explains that donations go to local charities, such as the Islington Foodbank – “the localness went down really well” – as well as providing the homeless street funders with the London Living Wage (it is hoped in future to also gain sponsors for the wages).

In addition, TAP plans to provide training and speakers to allow the fundraisers to build up skills in sales so that they can move into employment. “We wanted to put the generosity of Londoners to good use in a way that’s safe, quick and easy,” says Whitlock. To date, its devices have been set at £3 per tap; donors are given “thank you” cards with artwork from local artists. While London-based so far, she feels the model is perfectly applicable beyond here.

Sophie Green, recently recruited by the UK’s Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) from American Express as head of customer offer, believes there is the need to give potential donors the easiest way to donate. While contactless might still be less relevant in some countries, in the UK and other developed nations, it is becoming critical, she believes.

At the same time, she points out that while “contactless is a great facility to help end-causes”, it is just one component. There are also the implications for payments of regulations, particularly PSD2, she points out, plus other forms of funding, particularly crowdfunding, and other potentially relevant technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain.

The solutions

Set up in 2016, GoodBox looked at the challenge from the charity perspective, says O’Brien. It saw the need for one point of contact, the ability to purchase and rent devices, and to have consolidated analytics and affordable hardware that would suit different needs. At the higher end, it envisages large charities with networks of thousands of units, so its platform has remote monitoring, including alerts if a device goes offline.

On the donor side, GoodBox identified the power of story-telling, along the lines of TV adverts, says O’Brien, so there is the ability to conveying video and still imagery or messages on its devices.

There might also be a need to quickly change messages, such as in the event of a disaster, so new messages can be uploaded by charities to the central cloud-based portal and pushed out to all devices.

Where an organisation such as a church or supermarket supports multiple charities, there can be revolving displays and donations can be allocated to each.

“Technology-based solutions should be user-led,” says Hugh Goulbourne, senior associate at advisory business, The Social Innovation Partnership (TSIP). This includes the commissioning organisation as well as the actual user. It should be about how to make a difference to the person who needs it the most, he says, not about, for instance, reducing the cost of delivery.

“We are quite confident that this is the type of innovation that’s needed. But however we set up the giving experience, there has to be the same sort of safety and confidence between the recipient and the giver.”

One project TSIP is advising on is to bring the Helping Hearts contactless patched coats from the Netherlands to the UK, initially in London, Manchester and Liverpool.

The established payment heavyweights are also active. In particular, Barclaycard carried out a pilot in Q4 2016 with nine national charities and two museums. The Barclaycard donation boxes comprised a small card reader; a branded, hand-held box specific to each charity; and an accompanying payment acceptance app, connected to the reader via Bluetooth. Partners were brand design agency, Sprout, payment gateway provider, Payworks, and mobile payments specialist, Miura Systems.

Barclaycard has stated that the launch of a full charity box offering is planned for early 2018 as part of its mobile point-of-sale “Barclaycard Anywhere” range.

GoodBox emphasises the benefits of being a fundraising payments specialist and one-stop shop. It claims to be “actively engaged” with 180 charities, 40 museums, 15 hospitals and a number of banks in the UK, and with interest from at least seven other countries.

It has three devices, comprising a handheld GoodBox mini, which is contactless and chip and PIN-enabled; a larger unit with 7” LCD screen; and the standalone GoodBox Pro terminal. Chip and PIN-enablement allows donations above the maximum limit for contactless.

Sourced from China, GoodBox was careful about the supply chain for its devices. “We walked the floor of all the factories we’re using,” says O’Brien. It is now crowdfunding, ahead of the launch of its next version of devices in March 2018.

Donors can specify the amount they want to give or can choose a pre-set amount. GoodBox co-founder and COO, Francesca Hodgson, says, “a lot of times, because it is so convenient, people are happy to select the pre-set amount”. So far, a pre-set amount of £5 has been well received, she says, but points out that the pilots have mostly been in London to date so this might vary elsewhere.

GoodBox estimates that to date there has been an increase of around 24% in donations via contactless cards versus cash. For a museum, for instance, this means an average return on investment of one week; for a mobile device, it claims it is closer to nine hours. “The customer uplift more than justifies the cost,” says O’Brien.

CAF’s Green believes the technology can be applicable to most sized charities and it might be the smaller ones that are quickest off the mark. “To some degree, the beauty of digital transactions is that things are scalable, and smaller charities can often be more creative, it is a huge opportunity for them.”

Conclusion

TSIP’s Goulbourne describes contactless as bringing the charity and not-for-profit sector “up-to-date, especially for a demographic of under 35”, although points out that ever more people generally are “used to one or two touch payments”.

However, he emphasises that the solutions need to be cost-effective. For the Big Issue model, for instance, the cut taken by the payment company has to come out of the seller and/or the charity’s income. Ultimately someone pays somewhere along the line but in the pilots to date, it doesn’t look difficult to make the business case.

This article is also featured in the December 2017/January 2018 issue of the Banking Technology magazine. Click here to read the digital edition – it is free!